Following on – a bit later than I’d intended – from the initial rundown of the EU Election results, part two involves having a slightly closer look at how each party’s vote was distributed around the country. This always comes with the caveat that for this election local results don’t count for anything beyond their contribution to the overall figure, but they do indicate places where a given party might do particularly well or poorly when the next set of more local elections rolls around.

Note: I pressed a button on QGIS which I just assumed would neatly split results into bands of 8 councils (i.e. quarters), but it hasn’t quite done that in every case. Just trust that it knows what it’s doing and why, that’s what I always assume. Be aware that the bands for each party aren’t equal % widths,

Note 2: Yes, “Where Are the Votes?” is intended to be read in the style of Trinity “the Tuck”.

SNP

The major thing to note for the SNP is the shift in their support’s centre of gravity, from the north into the Central Belt. Whereas in 2014 areas like Moray, Perth and Kinross, Aberdeenshire and Highland were some of the SNP’s strongest areas, by 2019 they’ve fallen into the weaker side of the equation. Areas like Glasgow and Inverclyde went in the opposite direction, whilst already strong showings in the likes of North Lanarkshire and West Dunbartonshire were reinforced.

It is important to bear in mind that their vote share went up everywhere between these two elections – Aberdeenshire for example features some of the lowest SNP support whilst still seeing them win 0.1% more than they did in 2014. That in itself highlights that there’s been a huge shift in where the SNP vote is concentrated. However, it also backs up the point I made in the initial results post that this likely indicates a lasting loss of SNP support (relative to 2015/16) in some of their former rural heartlands, made up for by increased strength in urban areas.

The Brexit Party

Obviously no 2014 comparison for the brand-new Brexit Party, their vote is spread pretty much as you’d expect it. Northern and southern areas that had higher Leave votes than the Scottish average in 2016 plus a recent history of voting Conservative proved most fertile for the party. On the other hand, the urban west plus Stirling, Edinburgh and East Lothian proved least likely to vote for Farage’s lot.

Liberal Democrats

For the other big winners in this election, the Lib Dems, the overall spread of their vote looks pretty similar to 2014. The Northern Isles, Highlands, Aberdeenshire, Borders, Edinburgh and East Dunbartonshire are exactly the places you’d expect the party to record their strongest votes. There is a slight redistribution of the balance of votes from Dundee, Moray, Argyll & Bute, and Angus into East Renfrewshire, South Ayrshire, Aberdeen and West Lothian.

For the other big winners in this election, the Lib Dems, the overall spread of their vote looks pretty similar to 2014. The Northern Isles, Highlands, Aberdeenshire, Borders, Edinburgh and East Dunbartonshire are exactly the places you’d expect the party to record their strongest votes. There is a slight redistribution of the balance of votes from Dundee, Moray, Argyll & Bute, and Angus into East Renfrewshire, South Ayrshire, Aberdeen and West Lothian.

Conservatives

The Conservative’s pattern looks a little bit like the Brexit Party’s, with strong performances in the North East and South of the country, though they also still performed comparatively well in heavily Remain East Renfrewshire. There’s no shift in where their top 8 performances were in each election, though there’s a bit of a shuffle in the lower and middle ends of the scale. Weaker results in Edinburgh and East Dunbartonshire likely indicate voters returning to the Lib Dems in those areas, whilst a relative shift up the rankings for South Lanarkshire and East Ayrshire may show the Conservatives holding on a little better in areas the Lib Dems were less able to pick up pro-Union voters.

The Conservative’s pattern looks a little bit like the Brexit Party’s, with strong performances in the North East and South of the country, though they also still performed comparatively well in heavily Remain East Renfrewshire. There’s no shift in where their top 8 performances were in each election, though there’s a bit of a shuffle in the lower and middle ends of the scale. Weaker results in Edinburgh and East Dunbartonshire likely indicate voters returning to the Lib Dems in those areas, whilst a relative shift up the rankings for South Lanarkshire and East Ayrshire may show the Conservatives holding on a little better in areas the Lib Dems were less able to pick up pro-Union voters.

Labour

A measure of just how catastrophic these elections were for Labour might be to look at the difference in banding between 2014 and 2019. This their strongest performance this time of 16.4% would have been on the lower end of the 2nd worst tier of 2014 results. Additionally, for all that they came 1.1% ahead of the Greens overall, all eight of their worst performances were below the Green’s absolute bottom performance. Apart from Shetland and the Western Isles gaining a shade at the expense of the Highlands and East Renfrewshire, Labour show the most consistency of any party in how their vote was spread in both elections.

A measure of just how catastrophic these elections were for Labour might be to look at the difference in banding between 2014 and 2019. This their strongest performance this time of 16.4% would have been on the lower end of the 2nd worst tier of 2014 results. Additionally, for all that they came 1.1% ahead of the Greens overall, all eight of their worst performances were below the Green’s absolute bottom performance. Apart from Shetland and the Western Isles gaining a shade at the expense of the Highlands and East Renfrewshire, Labour show the most consistency of any party in how their vote was spread in both elections.

Greens

Although far less successful overall, the Greens experienced a similar phenomenon to the Lib Dems where their spread of votes narrowed from both ends – increasing in their worst 2014 areas but decreasing in their best. Like most parties there wasn’t a huge shift in the relative distribution of that vote, with strongest support in the Lothians, Glasgow, Stirling, the Highlands and Northern Isles, but weakest in Ayrshire and the rural North East. There was a slight redistribution to Dundee, Perth & Kinross, Dumfries & Galloway and the Western Isles from Aberdeen, West Dunbartonshire and South Lanarkshire.

Although far less successful overall, the Greens experienced a similar phenomenon to the Lib Dems where their spread of votes narrowed from both ends – increasing in their worst 2014 areas but decreasing in their best. Like most parties there wasn’t a huge shift in the relative distribution of that vote, with strongest support in the Lothians, Glasgow, Stirling, the Highlands and Northern Isles, but weakest in Ayrshire and the rural North East. There was a slight redistribution to Dundee, Perth & Kinross, Dumfries & Galloway and the Western Isles from Aberdeen, West Dunbartonshire and South Lanarkshire.

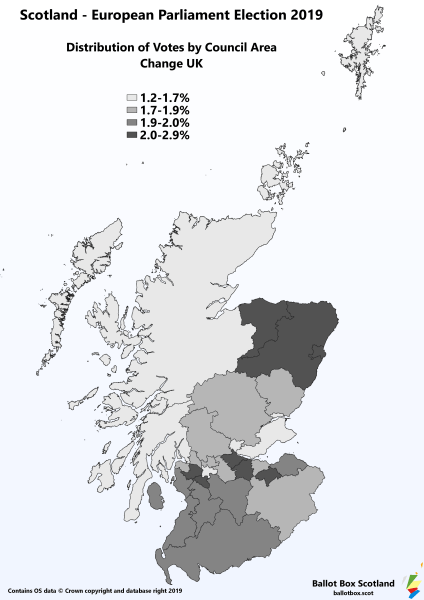

Change UK

2019’s other new kids on the block, recent splits from Change UK may be leaving them as little more than a minor footnote in the UK’s political history. Perhaps because of their very low support, there doesn’t seem to be much rhyme nor reason to how it was distributed. East Renfrewshire makes a little bit of sense as the area their longest lasting lead candidate sits as a councillor, but I’m not sure what links Renfrewshire and Moray, or Aberdeen and Midlothian, or why their next strongest performing councils are a cluster in the South West plus East Lothian. Very weak performances in Dundee, Glasgow and Fife make a bit more sense, but it’s actually quite remarkable for any party to come as low as 1.2% in Orkney and Shetland, which have otherwise tended to be quite forgiving places for small parties.

2019’s other new kids on the block, recent splits from Change UK may be leaving them as little more than a minor footnote in the UK’s political history. Perhaps because of their very low support, there doesn’t seem to be much rhyme nor reason to how it was distributed. East Renfrewshire makes a little bit of sense as the area their longest lasting lead candidate sits as a councillor, but I’m not sure what links Renfrewshire and Moray, or Aberdeen and Midlothian, or why their next strongest performing councils are a cluster in the South West plus East Lothian. Very weak performances in Dundee, Glasgow and Fife make a bit more sense, but it’s actually quite remarkable for any party to come as low as 1.2% in Orkney and Shetland, which have otherwise tended to be quite forgiving places for small parties.

UKIP

Look, I’m not really sure why QGIS decided it had to be particularly weird about UKIP, but it did. With their vote completely cannibalised by Brexit, there are broad similarities between where each party did the best, with UKIP largely mirroring Brexit’s concentration in the North East and Dumfries & Galloway, with corresponding poor performances in some of the west Central Belt, Edinburgh and East Lothian. The fact West Dunbartonshire was bottom band for Brexit but second band for UKIP looks peculiar, but that’s likely just a combination of UKIP’s low vote share exaggerating small differences, plus my eye being drawn to where I grew up.

Look, I’m not really sure why QGIS decided it had to be particularly weird about UKIP, but it did. With their vote completely cannibalised by Brexit, there are broad similarities between where each party did the best, with UKIP largely mirroring Brexit’s concentration in the North East and Dumfries & Galloway, with corresponding poor performances in some of the west Central Belt, Edinburgh and East Lothian. The fact West Dunbartonshire was bottom band for Brexit but second band for UKIP looks peculiar, but that’s likely just a combination of UKIP’s low vote share exaggerating small differences, plus my eye being drawn to where I grew up.

There’s just one final thing to look at before waving goodbye to the EU elections (and in theory the MEPs elected in them, if Brexit ever does go ahead) – possible alternative voting systems. That piece will come later this week.