The clue is kind of in the name, but Local Elections are by far the least useful to analyse purely at either the national or even whole council level. Even within a single town or city, there can be wide variations in voting patterns. In this page I go into a bit more of the detail in terms of how well the parties did at ward level. Given there are 354 wards in Scotland and no party stands in them all, national vote share figures can also be slightly deflated compared to what “true” support may be. As such, I’ve worked out how well each party fared in the wards they did stand; albeit with the caveat that figure might also be inflated, so look for truth in the middle.

Note: The scales on each of these maps does vary to best highlight each party’s spread of the vote. It wouldn’t be helpful, for example, to show Green or Lib Dem votes on a scale with 10% increments given their national vote share was well below that.

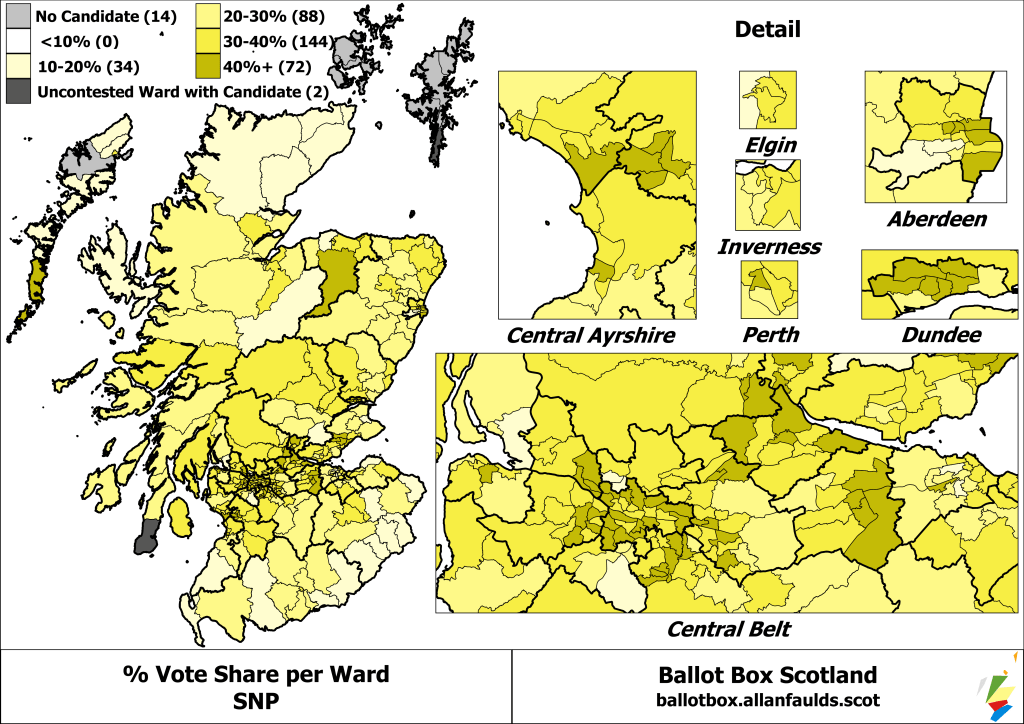

SNP

- Wards with at least one SNP councillor – 331 (93.5%)

- Wards contested by the SNP, but not won – 9 (2.5%)

- Wards not contested by the SNP – 14 (4.0%)

It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise that the SNP won a seat in almost every ward in the country. At least one SNP candidate could be found in every mainland ward, with only the islands presenting gaps in their slate; even then, they made the best attempts of any party, leaving only Orkney without any SNP presence.

Unlike Labour and the Tories, the SNP since 2011 have proven strong in all corners of Scotland. However, the SNP’s overall pattern of votes and councillors reflected a continuing redistribution of the party’s vote from the rural North East into the Central Belt and urban areas. They made up for big losses in their traditional strongholds of Angus, Aberdeenshire and Perth & Kinross by swelling their numbers in cities like Glasgow and Aberdeen and councils in the urban west such as Renfrewshire and West Dunbartonshire.

You can see that redistribution of votes quite clearly in this map; only two wards outside of the big cities and Central Belt show the dark colouring of a 40% or more vote share, both in Moray. In 2012, those dark patches would have been further north and more rural. Still, even where the SNP were at their weakest – basically the far north and far south of the country – they didn’t poll any less than 10%.

You can see that redistribution of votes quite clearly in this map; only two wards outside of the big cities and Central Belt show the dark colouring of a 40% or more vote share, both in Moray. In 2012, those dark patches would have been further north and more rural. Still, even where the SNP were at their weakest – basically the far north and far south of the country – they didn’t poll any less than 10%.

Across the wards they stood in, the SNP recorded a total vote share of 32.6%, vs 32.3% overall.

Conservatives

- Wards with at least one Conservative councillor – 243 (68.6%)

- Wards contested by the Conservatives, but not won – 94 (26.6%)

- Wards not contested by the Conservatives – 17 (4.8%)

The Conservatives contested almost as many wards as the SNP; a full mainland slate, only Orkney missing candidates entirely. Riding the wave of their ongoing revival, they elected a councillor in most of them too. In 2012, there were only a handful of councils the Tories had no representation on; but there were plenty they had very little. That all changed in 2017, with even Glasgow electing a sizeable group, and their first councillors in West Dunbartonshire’s history.

That said, those councils and others in the West Central Belt were still their weakest areas, with plenty of gaps in comparison to the South and North East where they won a spot in every ward.

Bringing their votes into the equation explains those gaps – across the Central Belt, in the Highlands and Dundee, they polled below 20% in most wards. Meanwhile the Borders, Perthshire, Angus and Aberdeenshire are deepest blue, reminding us how much the scales have tilted away from the SNP (and Lib Dems, for the Borders) in those areas. There are actually a few wards in amongst those where the Conservatives underestimated their support, and would be sitting with a handful more councillors had they stood a second candidate, for example in Angus and even around Helensburgh in Argyll & Bute.

Bringing their votes into the equation explains those gaps – across the Central Belt, in the Highlands and Dundee, they polled below 20% in most wards. Meanwhile the Borders, Perthshire, Angus and Aberdeenshire are deepest blue, reminding us how much the scales have tilted away from the SNP (and Lib Dems, for the Borders) in those areas. There are actually a few wards in amongst those where the Conservatives underestimated their support, and would be sitting with a handful more councillors had they stood a second candidate, for example in Angus and even around Helensburgh in Argyll & Bute.

Across the wards they stood in, the Conservatives recorded a total vote share of 25.6%, vs 25.3% overall.

Labour

- Wards with at least one Labour councillor – 214 (60.5%)

- Wards contested by Labour, but not won – 91 (25.7%)

- Wards not contested by Labour – 49 (13.8%)

Although the loss of a third of their councillors was a blow, the Labour party were by no means wiped out. Almost every ward in the Central Belt and urban Fife, the party’s long-standing strongholds, still returned at least one Labour councillor. The most notable exceptions to this can be found in western Edinburgh and a particularly bruising reduction to just two councillors in East Dunbartonshire.

There may be more grey on this map than for the SNP or the Conservatives, but Labour still stood in a respectable 86.2% of Scotland’s wards. Only the islands didn’t have any Labour candidates to vote for, and the mainland wards they didn’t contest were exclusively rural.

The reasons for that are immediately apparent here; except for Dumfriesshire, Labour barely registered in rural Scotland. Although they have hit lows in the likes of Aberdeenshire and Moray, this isn’t exactly new information for Labour, or unique to their Scottish wing. Labour have always been a party of urban and industrialised areas.

The reasons for that are immediately apparent here; except for Dumfriesshire, Labour barely registered in rural Scotland. Although they have hit lows in the likes of Aberdeenshire and Moray, this isn’t exactly new information for Labour, or unique to their Scottish wing. Labour have always been a party of urban and industrialised areas.

Most notable about that map though is that Glasgow is relatively pale. True, most of the city still saw a Labour vote above 30%; but they didn’t cross 40% in any ward. They didn’t fall as far there as many expected, but it was still a remarkable defeat for them. Their best performing wards are scattered about the Central Belt in towns like Kilsyth, Blantyre, Fauldhouse and Cowdenbeath.

Across the wards they stood in, Labour recorded a total vote share of 21.8%, vs 20.2% overall.

Liberal Democrats

- Wards with at least one Lib Dem councillor – 63 (17.8%)

- Wards contested by Lib Dems, but not won – 173 (48.9%)

- Wards not contested by Lib Dems – 118 (33.3%)

“Static” is the general trend for the Lib Dems in Scotland post-2011, generally holding on to what they have but not showing signs of recovery, winning 67 councillors across 63 wards. As with the Scottish Parliament elections though, that relative stability nationally disguised their weakness in many local areas. Gains in their remaining strongholds like East Dunbartonshire and the west end of Edinburgh were offset by losses in other traditional Liberal areas like Fife and the Highlands. The Borders in particular proved calamitous for the party; since 2007, they’ve dropped from 25% and 10 seats to 8% and 2 seats, as well as losing the MP, constituency MSP and even the regional MSP for the area.

Similarly, the 236 wards they contested across Scotland weren’t neatly spread. In addition to the three island councils, there were five mainland councils they didn’t put up a single candidate; Falkirk, North Lanarkshire, and all three Ayrshires. They also didn’t stand a full slate of candidates in Glasgow for the first time since STV was introduced, and saw an end to 40 years of Liberal representation in the city.

Looking at the distribution of votes per ward, you can clearly see the outlines of their two mainland Holyrood constituencies there as the darkest patches of Fife and Edinburgh. There are also patches of particularly strong support in Aberdeen, East Dunbartonshire, Highland, and even Dundee. However, huge swathes of the Central Belt and what could be described as mid-rural Scotland recorded continuing low support for the Lib Dems.

Looking at the distribution of votes per ward, you can clearly see the outlines of their two mainland Holyrood constituencies there as the darkest patches of Fife and Edinburgh. There are also patches of particularly strong support in Aberdeen, East Dunbartonshire, Highland, and even Dundee. However, huge swathes of the Central Belt and what could be described as mid-rural Scotland recorded continuing low support for the Lib Dems.

Across the wards they stood in, the Lib Dems recorded a total vote share of 9.4%, vs 6.9% overall.

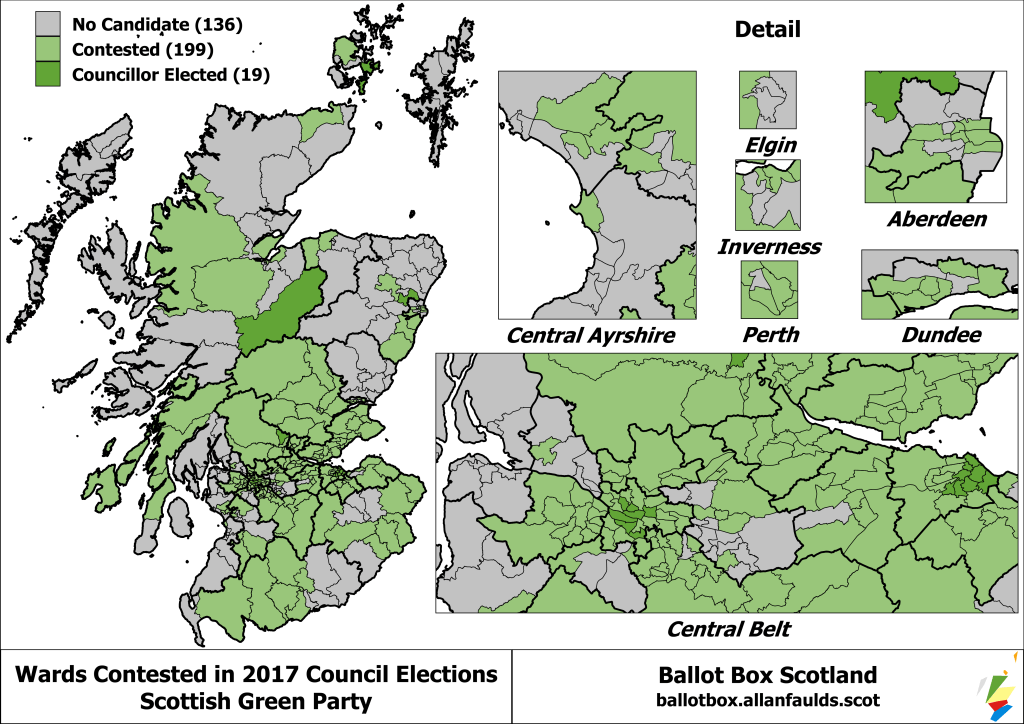

Greens

- Wards with at least one Green councillor – 19 (5.4%)

- Wards contested by Greens, but not won – 199 (56.2%)

- Wards not contested by Greens – 136 (38.4%)

Although it didn’t prove to be much of a breakthrough year in terms of the number of councillors actually elected, 2017 did see the Greens put themselves on the local election map like never before. In 2012, the party only contested around 80 wards. Last time that figure was 218 wards – 61.6% of the total, representing 69.9% of voters.

In the 2007 and 2012 elections, they only presented a full slate of candidates in Glasgow and Edinburgh. This time around a total of nine councils saw a full Green slate, with two other councils coming just one candidate short. By contrast, four councils didn’t have a single Green – Inverclyde and Angus on the mainland, plus (unsurprisingly) Shetland and the Western Isles. Notably, however, the Greens are the only major party represented on Orkney Islands council. That means that despite standing in fewer wards than the Lib Dems, the Greens had a presence in more councils.

In terms of results per ward, the map above makes clear why the Greens have struggled a bit to win seats even under PR. Their vote share is quite heavily concentrated in Glasgow and Edinburgh, with only a few hot spots scattered outside. STV for 3-4 members isn’t a particularly proportional form of voting, so racking up 3-6% results spread nice and evenly doesn’t count for much.

Apart from the wards where they won councillors, you can spot a few areas of potential promise. Although they lost their councillor there, Midlothian is still an overall quite strong area. Stirling, Clackmannanshire, the Highlands, Moray and Aberdeen also showed some solid results.

Across the wards they stood in, the Greens recorded a total vote share of 5.9%, vs 4.1% overall.

Holyrood 5

Having looked at each of the 5 Holyrood parties individually, it’s worth a quick look at the overall picture. Although each party contested most wards, not every ward saw voters having the option to vote for all of them.

In fact, only 44.6% of wards had a full selection – though those wards accounted for 53.4% of the votes cast on the day. Where the major parties went head to head, the results were;

- SNP – 32.8%

- Conservative – 24.6%

- Labour – 21.9%

- Lib Dem – 9.1%

- Green – 6.4%

Minor Parties

For the sake of completion, it’s worth having a wee look at some of the smaller parties that contested the local elections. These only have maps showing the wards they stood in, as their support and contest rates were so low it’s not worth breaking down.

Starting with UKIP, they were only able to stand in 44 wards – just 12.4% of the total. They had stood almost as many candidates for the UK Parliament election in 2015, so the fact they couldn’t do much better than that for local elections shows how diminished they were by Brexit. Bear in mind too that despite this being the third election via (semi) proportional representation for councils, UKIP have never won a councillor in Scotland, unlike in England and Wales. A single MEP in 2014 remains the extent of UKIP’s electoral success here, which may help further contextualise their complete lack of impact.

Even more curiously, almost all of their candidates were to be found in the Central Belt, rather than in the likes of Moray, Aberdeenshire, Angus or Galloway, the kind of places that have historic fishing communities considered to lean Brexit. Moray in particular was very nearly Scotland’s only Leave voting council area in 2016. If anywhere was ripe for UKIP’s message, even after they didn’t seem necessary anymore, it would have been there, but not a Kipper to be caught!

Across the wards they stood in, UKIP recorded a total vote share of 1.0%, vs 0.2% overall.

Next up the newcomers in the Scottish Libertarian Party. The most recent in a line of extremely fringe avowedly right-wing pro-independence parties, the Libertarians first appeared on the scene at the Holyrood elections in 2016. They contested a somewhat surprising 6.2% of the wards the following year – including, bizarrely, a full slate in East Ayrshire. Who’d have thought Cumnock was home to a secret Libertarian cell?

Across the wards they stood in, the Libertarians recorded a total vote share of 0.56%, vs 0.04% overall.

Turning leftwards, TUSC candidates were to be found in 5.4% of wards – overwhelmingly in Glasgow, and in Dundee where co-operation with the SSP saw a Left candidate in every ward. Their slate was rounded out with a couple of candidates in Renfrewshire, and one apiece in North Ayrshire, East Lothian and West Lothian.

Across the wards they stood in, TUSC recorded a total vote share of 1.2%, vs 0.1% overall.

Tommy Sheridan’s ego vehicle has fallen quite far since, well, he single handedly brought down the traditional Left in Scotland. Just 4.5% of wards had a TOMMY SHERIDAN HOPE OVER FEAR candidate on the ballot. Apart from a far flung Aberdeen candidate, these were all in the Central Belt. Oddly, Greater Pollok was not one of them, despite Pollok being his home ground; though the Cardonald ward overlaps with the ward he represented in the 90’s, so perhaps their energy was focused there.

Across the wards they stood in, Solidarity recorded a total vote share of 0.83%, vs 0.05% overall.

Finally, the SSP and RISE. Having been shattered by Sheridan in the 2003-07 Scottish Parliament, the SSP have also been in terminal decline. In the previous two elections they did have a councillor elected in the form of Jim Bollan in West Dunbartonshire – however, he was involved in setting up the West Dunbartonshire Community Party there in 2017, depriving the SSP of their last elected representative. They competed in the 2016 Holyrood elections under the RISE banner, hoping to capitalise on Left-Independence support.

When that alliance failed entirely to make an impact, the SSP opted to withdraw, and RISE seemed too stunned to organise for local politics. In the end, only 4.2% of wards had a candidate from either group; and only one of those, in Motherwell, stood as RISE. However, they proved the Left grouping with the biggest presence outside the Central Belt, with candidates in Inverness and in Nairn.

Across the wards they stood in, the SSP/RISE recorded a total vote share of 1.35%, vs 0.06% overall.