It’s a quiet time to be an elections and polling project. Polling is currently monthly, at best, and we don’t have any council by-elections until October thanks to the pandemic. That means I have a lot of time on my hands to do things like nurse an ongoing grudge against poor journalistic practices. I’m not entirely sure why, but there are two particular misconceptions about Holyrood’s voting system that pop up frequently amongst journalists (and, of course, the wider public).

Complexity

Perhaps because the UK as a whole is still so used to (the blot on democracy that is) First Past the Post, the Holyrood voting system is almost invariably described by journalists as “complex”. It’s an almost Pavlovian response. A journalist writes something like “the Scottish Parliament voting system”, and then immediately also thinks “ah – complex.” This is a lazily formulaic description that all too often takes the place of meaningful attempts to explain what is really quite a simple system.

With apologies, as he is an otherwise excellent journalist, I’m going to pick on the BBC’s Philip Sim in this post, as it was his article that I saw most recently. Here’s his brief description of AMS:

The “additional member system” features 73 constituency seats, elected on a traditional first past the post (FPTP) basis, and 56 “list” seats scattered across eight regions.

The system itself is complex, but in short the more constituency seats you win, the harder it is to win list seats.

It’s not just that the word “complex” hasn’t added anything to the explanation, it’s that there isn’t an explanation. Why does winning lots of constituencies make it hard to win list seats? What’s particularly annoying here is the word “proportional” isn’t used once in the entire article. Readers are missing a key principle of the system, which is left breezily unexplained as “complex”. With the same number of words, here’s my version:

The “additional member system” features 73 constituency seats, elected by traditional first past the post (FPTP), and 56 proportional “list” seats in eight regions.

List seats ensure proportionality within each region, so a party that wins many constituencies doesn’t usually need list seats for their fair share overall.

Sure, some of those words are a bit longer, but this version doesn’t talk down to voters. It makes clear the system is proportional. It explains that means parties that do well in constituencies don’t need list seats – but the “usually” leaves open that they sometimes do. Crucially, you don’t need to explain the maths of the D’Hondt method to voters in order to communicate the basic principles of the system.

Even if you do get into it, the maths you need to understand AMS is just addition and division. “Within each region divide each party’s share of the vote by one more than the total number of constituency and list seats they’ve won so far. The party with the highest number wins the next list seat. Add to their total and repeat the process.” This is a level of mathematical ability people are typically expected to leave primary school with, just with bigger numbers.

Is AMS more complex than FPTP? Sure, in the same way Stirling is further north than Glasgow. Does that mean the system itself is actually complex? No, in the same way Stirling isn’t in the North of Scotland.

The SNP Broke AMS in 2011

After I’d grumped on Twitter about “complex” and watched some more of Canada’s Drag Race (I want nothing but good things for Ilona Verley), I read further and found the article also had another of my bugbears – a claim that the SNP “broke” the system in 2011 by winning a majority. This is perhaps the more serious misconception, as rather than being lazy it’s just plain wrong. People seem to be unable to get past their perception of what the system is intended to do, to understand how it was actually implemented.

The intent of AMS is, of course, to deliver proportionality. A natural consequence of that is that it makes it hard for a party to win a majority. Contrary to conspiracy theories, this wasn’t a deliberate “keep the SNP down” ploy. Any credible form of proportional representation, which the SNP have long supported, has this effect. However, it was also intended to limit that proportionality to regions rather than nationwide. This may have been to ensure some degree of local connection in a country very used to that, or to specifically advantage larger parties, or a combination of both.

Regardless, this actually ensured that there was more potential in the system for majority government. In Germany and New Zealand, for example, the system works nationally. Proportionality in New Zealand is across all 120 seats. In Scotland the proportionality is across between 15 and 17 seats. That difference matters, as the more seats available, the more proportional the system will be. For example, 10% of the vote won’t normally win anything if there are 5 seats up for grabs, but it’ll win one if there are 10 available. It’ll win 2 seats out of 20, but if there are 16? It can go either way depending on other party results, and small regional disproportionalities can add up to big ones nationally.

When the SNP won their 2011 majority, it surprised everyone based on the general idea that majorities are unwinnable. But according to the actually implemented rules 2011 was the least broken of any Holyrood election yet. I’ve written about the concept of “overhang” before, which is when a party wins too many constituencies for their vote share, but it’s useful as a key measure for whether AMS has actually been “broken”.

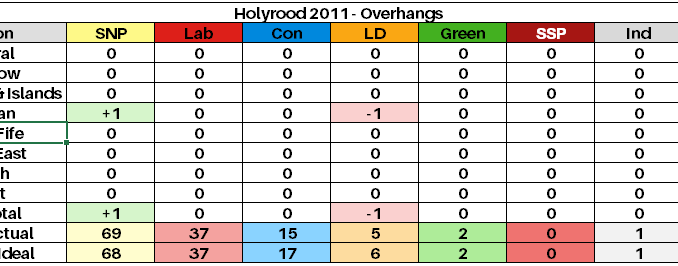

As evidenced by the fact they won list seats in 7 of the 8 regions, which doesn’t happen if you have too many constituencies, the SNP had very little overhang in 2011. The only case was in Lothian, where they won one constituency too many and thus locked the Lib Dems out of the last list spot. AMS was thus almost flawless at that election – and it was again in 2016, when it was Mid Scotland & Fife the SNP had one seat too many, and Labour lost out.

Overhang had been higher at earlier elections, and there’s a full list of overhangs in this Twitter thread. In short, it had been 2 seats wrong in 2007, and 7 seats wrong in both 2003 and 1999. Technically 2003 was 9 wrong, but there were two that cancelled each other out nationally. When winning a majority, the SNP actually broke the system far less than Labour did as a minority. That’s because the SNP’s vote share was higher and more evenly distributed than Labour’s ever was.

The fact journalists are out there constantly making these mistakes isn’t, in the grand scheme of things, a crisis. Our democracy isn’t going to live or die by whether people understand that the 2011 election worked almost perfectly, or that the voting system uses primary school arithmetic.

It does though add in a small way to the mystique around Holyrood as this quite peculiar institution with byzantine rules, versus the crystal clarity of solid, transparent Westminster, when of course in general terms the opposite is true! If journalists, at best, are resorting to lazy clichés or, at worst, haven’t actually taken the time to understand the voting system themselves, they are doing the public a disservice. They can and should do better.

And with that in mind, if any media organisation wants to invite me in to deliver a seminar on this, my rates are very reasonable indeed…